In general, wood engravings may not be eye-catching if they are placed in prestigious museums. Not only do they lack color, but also they are not original drawings. Based on conservation standards, prints can usually be displayed under light for no more than fourteen weeks before they are sent back to the dark storage rooms. Therefore it is actually very rare to see a comprehensive collection of Homer’s engravings displayed in one instalation.

Although Homer quit working as an illustrator in 1870’s and never went back, those engravings (made by someone else) covered quite a time span of his career. There are works as early as the civil war era and some date to the late 1870’s (such as “breeze up”). But the works done for the Harper’s Weekly highlights the exhibition. After all these works were done by Winslow Homer who came out of the Bufford’s workshop with fine lines that are quintessential to a wood block artist.

Some early double-paged prints seem to be directly detached from the magazine so that some have holes in the middle while others bear visible creases and wrinkles. Additional new copies of the magazine contents are displayed beside those prints. But looking through those wood engravings from Harper’s Weekly, one can easily feel unimpressed. Those B&W pictures are far away from his powerful Proust’s Neck crushing wave scenes. They were strict in both techniques and subjects; the figure drawings are more primitive and tightly controlled. (His late marine paintings, in contrast, grow into their own world.)

But a close examination of the works shows the opposite: In my mind, such a unique experience as a frontline illustrator defined Homer as a painter.

In the first place, viewers are naturally drawn into the contents of the pictures. Homer didn’t beautify or glorify the war and the soldiers. He did depict the battle scenes: A Bayonet Charge was one of the most disturbing drawings of all, in which soldiers from both sides, running out of the bullets, fighting as close to the enemy as to death. But most were not. It could be because of the propaganda purpose, or censorship burden; however, no matter for what reason behind it he added a glow of humanity for the soldiers. In “A Card Game”, there was a Bruegelian merrymaking atmosphere, even though viewers know there must be some grin battle looming ahead of the short feast. “Sleeping on their Arms”, was published in 1864, but no victory could be sensed. Instead the harshness was suffused into the winter scene. Sleeping soldiers were tired, so were the few on duty. However, the comradeship sparked out of the bald trees and bare sleeping ground. Above all, Homer focused on the soldiers who underwent the crudeness and threatening that readers stayed back could not imagine.

Those pictures provided no clue that his later style would be from the content perspective. Throughout his career, Homer was gradually drawn to the mighty nature that eventually all human were obliterated from his paintings. For him, moon, rocks and waves provided enough dramas for a soul of solitude. However, as a painter, Homer’s growth was more linear than disruptive. If one can move away from what was drawn in the picture and focus on how they were drawn instead, he can easily feel the linkage among his paintings: the design.

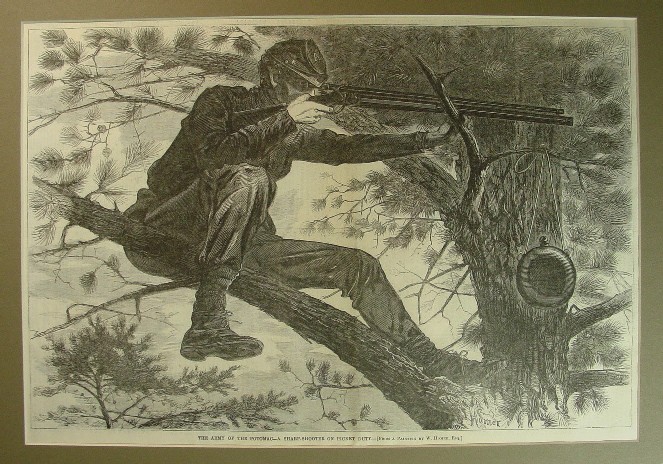

Several of Homer’s late works bears remarkable directness no matter what the subjects are. In “After the Hurricane”, the slightly tilted human figures were isolated from the sea by the wreck. There were no devastating nature scenes, but the image was effectively narrative by Homer’s choice of the boat which was placed with the opposite diagonal angle and his choice of body gesture which recalls classical reclining figures. The relative close distance brings up both dignity and sorrow from the tragedy. In “Right and Left”, viewers witness the process of the death from the two ducks. Such closeness can be valid only if viewers take the imaginary duck’s point of view, thus Homer brings down the viewer into the action. Then the hunter, no matter how small he has been drawn, takes the substantial meaning to balance the picture. Even in those Proust’s Neck pictures, the directness and boldness of paint brush cannot disguise his marvelous composition which is at once both natural and authoritative. Back to those civil War pictures, the soldiers were drawn in groups and forms of human figures gave away to more important overall composition. In most cases, he brought up the view closer so that there was a strong sense of narrative. Although he used lines succinctly and efficiently, he gave great detail to the center of the story and used airy perspective to render the background if necessary. No other early works than his most successful drawing “The Sharpshooter” could more effectively demonstrate Homer’s consistency as a designer. Here, we see the sniper from the bird angle, just like how we perceive those ducks. In both cases, Homer chose the perspective that were the most impossible yet the most narrative. High in the air, we observe of the sniper, in silence and in awe and expect the inescapable death execution, which he painted again more than 40 years later.

Secondly, although there was no record of how close Homer were to the battle scene, no one could walk out of the most bloodiest war in history without being changed. Civil War was the last war in history that infantry still marched out of the trench toward the enemy and the casualty lined up with every step they made. At the same time, the long-distance weapon was also first brought up to the military so that battle killing can be as remote and cold-blooded as murder. Homer’s “The Sharpshooter” differs from the rest in that here the soldier was drawn with a machine-like coldness. He can be observed, but not approached. He can be drawn, but not depicted. The gun, the half-shaded face showed a moment of deadly silence. Almost out of nowhere, now human can be killed without blood-shed or desperate cry's. Life has never become more fragile than ever before.

After the civil war, Homer’s ostensible subjects changed: soldiers became peasants or fishermen. But the nature didn’t grow more amenable. Instead, it still keeps its mighty power, as deadly as the rifle in the sharpshooter. Against this rugged nature, those ordinary people bear the same reticence and solitude as those soldiers. They are unnamed, uncharacterized, and unassuming, because in front of the unconquerable nature, the fragile humans struggle.

No classical, allegorical or historical topics interested Winslow Homer. Instead he chose the unpredictable commune between human and nature. Death or the hint of death (such as in “Saved” or “The Wreck”), which Homer may have witnessed as early as in war period, surfaced time and again in his paintings. In those paintings, the human beings, no matter how mundane, are depicted as hard-working, taciturn and serious in spite of all foul or malicious may happen ahead. He is now regarded as one of the most authentic American painters. And he deserves it.