Thurs., Oct. 23, 6:00–8:00 p.m. CMA, Call 412.622.3325 to register. LINK

There are three sideboards in existence known to be by Pittsburgh cabinetmakers. Undoubtedly there are more out there waiting to be discovered. One is seen in this short video. Although you can't see them in the video, this sideboard has two carved panels that sat on either side of the mirror. This carving is present on each of the three sideboards. The cabinetmakers of which are William Alexander, Henry Beares and Benjamin Montgomery. The similarities in the carved panels, especially in the Alexander and Beares sideboards are striking, so much so that during an initial inspection it can easily be concluded that the pieces came from the same shop. Another more likely possibility (since the sideboards are signed) is that a talented carver worked for a number of shops. That carver could have been Joseph Woodwell.

This particular sideboard is not known to have a signature. Unlike the other examples, this one contains some egyptian revival details including the feet and black marble in the center. It is also of an unusually large size.

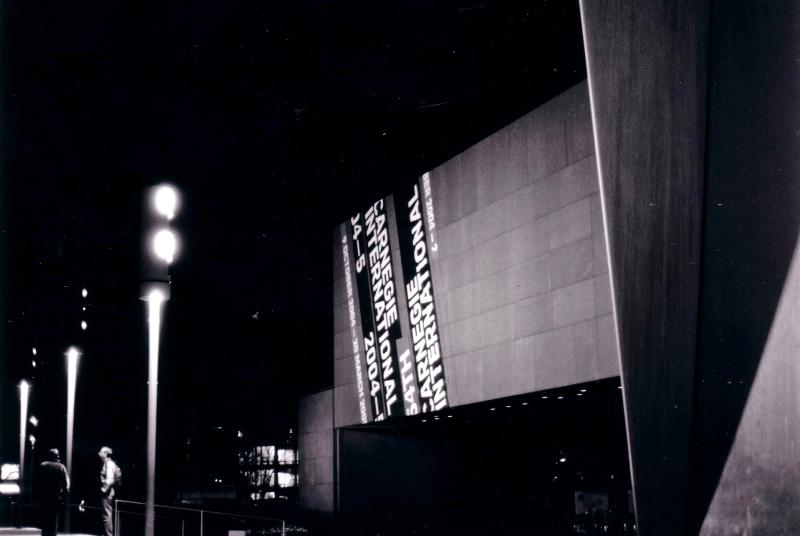

The Henry Beares sideboard is on view at the Carnegie Museum of Art. The William Alexander sideboard can be see in Wendy Cooper's Book, Classical Taste in America.

Can't make it to the Brooklyn Museum of Art? Is the Westmoreland out of reach? Visit our galleries and find some highlights of some of the country's great art museums. Included are selections from the Carnegie, Met, National Gallery and more.

Can't make it to the Brooklyn Museum of Art? Is the Westmoreland out of reach? Visit our galleries and find some highlights of some of the country's great art museums. Included are selections from the Carnegie, Met, National Gallery and more.

In the Hall of Architecture sits a smaller replica of the Parthenon created by students at Carnegie Mellon University, a school as endeared to Andrew Carnegie as the Museum.

In the Hall of Architecture sits a smaller replica of the Parthenon created by students at Carnegie Mellon University, a school as endeared to Andrew Carnegie as the Museum.

The current special exhibition at Carnegie Museum of Art provides a rare opportunity to view 75 American drawing and watercolors collected by the first director of Carnegie Institute of Art (John Beatty) during the first two decades of the 20th century. Based on a museum conservator’s comment, ideally paper works should not be exposed under light for more than 16 weeks per year, thus such treasure has never be integrated into the permanent collection in the museum. Among them, there are works by Winslow Homer, James McNeill Whistler, William Glackens, and Frederick Childe Hassam.

The works by Childe Hassam are mostly pencil and ink drawing. He chose different types of paper to provide the prime color for each work: some brown, some black and of course some white. The effect in general is bold and almost graphically decorative. In particular, he took advantage of the inherent contrast between ink and colored paper to emphasize light and shadow: some more protruding, some more coherent, depending on the similarity between color tones.

Homer started his career as an illustrator for Harper’s weekly. His pencil drawings are quite unique and interesting. But in my mind, it is his water-colors that should be valued the most since they have not been equaled ever since. In the current exhibition, the rare occasion provides two works of his famous theme: Proust’s Neck: one in pencil drawing and one in water-color. Both are efficient and foreboding. The water-color, eliminating the view of sea, projects the anxiety of waiting by carefully scaling the people with the nature. In contrast, the pencil drawing is more economical. He did not try to convert the value of colors into black and white, thus the figures in the drawing are exposed to a world rawer and barer.

It surprised me that Frederick Church sketched two mermaids holding a skull, something that is beyond the scope of accuracy and clarity that he’s familiar with. On the other hand, it does make sense that it was the painter who sketched the unseen and magical, endured all the inconvenience and sufferings to paint exotic scenes of both Arctic and South America.

Thomas Moran’s fondness of light effect is obvious on his only drawing in the exhibition. On the same wall, a pencil drawing of trees by Sanford Gifford bears the distinctive hazy and suffuse characteristics.

Lastly, a work by John Beatty’s contemporary and friend Alfred S. Wall also surprised me. As one of the initial trustees to the Carnegie Institute, his oil works are displayed at both Carnegie Museum of Art and Westmoreland Museum of Art. Among Wall family, I like A. S. Wall the most. William Coventry Wall is too meticulous and controlled while A. Bryan Wall is loose in paint brush while tight in subjects. The scene of Western Pennsylvania under A. S. Wall is mundane, un-idealized. It is not totally untamed, yet not luminous or sensational either. Instead, in that small picture on the middle of the wall, Wall painted the diminishing scene of uncultivated nature with traces of human beings, and infused them with a sense of nostalgia.

Such scene may be forever gone in the current Pittsburgh metro area, but through the carefully preserved artworks it can be still be imagined and appreciated, until Oct 7, when they are put back into storage.